Grieving and Achieving: What It Means to Build While Holding a Decade of Loss

This season, I find myself holding two truths at once: I am grieving, and I am achieving. And for the first time, I’m allowing both to be true without apology.

As I prepare to graduate from the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses Program, as new opportunities open, and as the next era of MINDART emerges, I’ve been sitting with a heaviness I can no longer ignore. On Friday, November 29, it will be ten years since the passing of one of the most important people in my life — my friend, my creative counterpart, and the person whose belief in me shaped more of my journey than most will ever know: Dro.

Image capture: Dro and I spending the holidays together after my return from Germany. Photographed November 2013.

Ten years.

A decade.

A full cycle of becoming.

People see the milestones. The growth. The creative work. The events. The wins. What they don’t see is how grief quietly shapes the architecture of a life — how it becomes the soul of your purpose long before you understand that’s what’s happening.

Before MINDART existed, before I ever used the words “creative wellness,” before I had a process, a brand, a team, or even a strategy, Dro and I used to talk in private about what it would look like to build a space where creatives could thrive, be nurtured, and be seen. We didn’t have a blueprint then — just a shared truth that artists deserve care, community, and room to breathe.

When he passed, that vision didn’t disappear.

It transformed.

His loss birthed CROWN, my first body of work honoring the intersection of art, identity, and healing. And CROWN became the foundation for MINDART, which has now served more than a hundred artists, dozens of organizations, and countless community spaces.

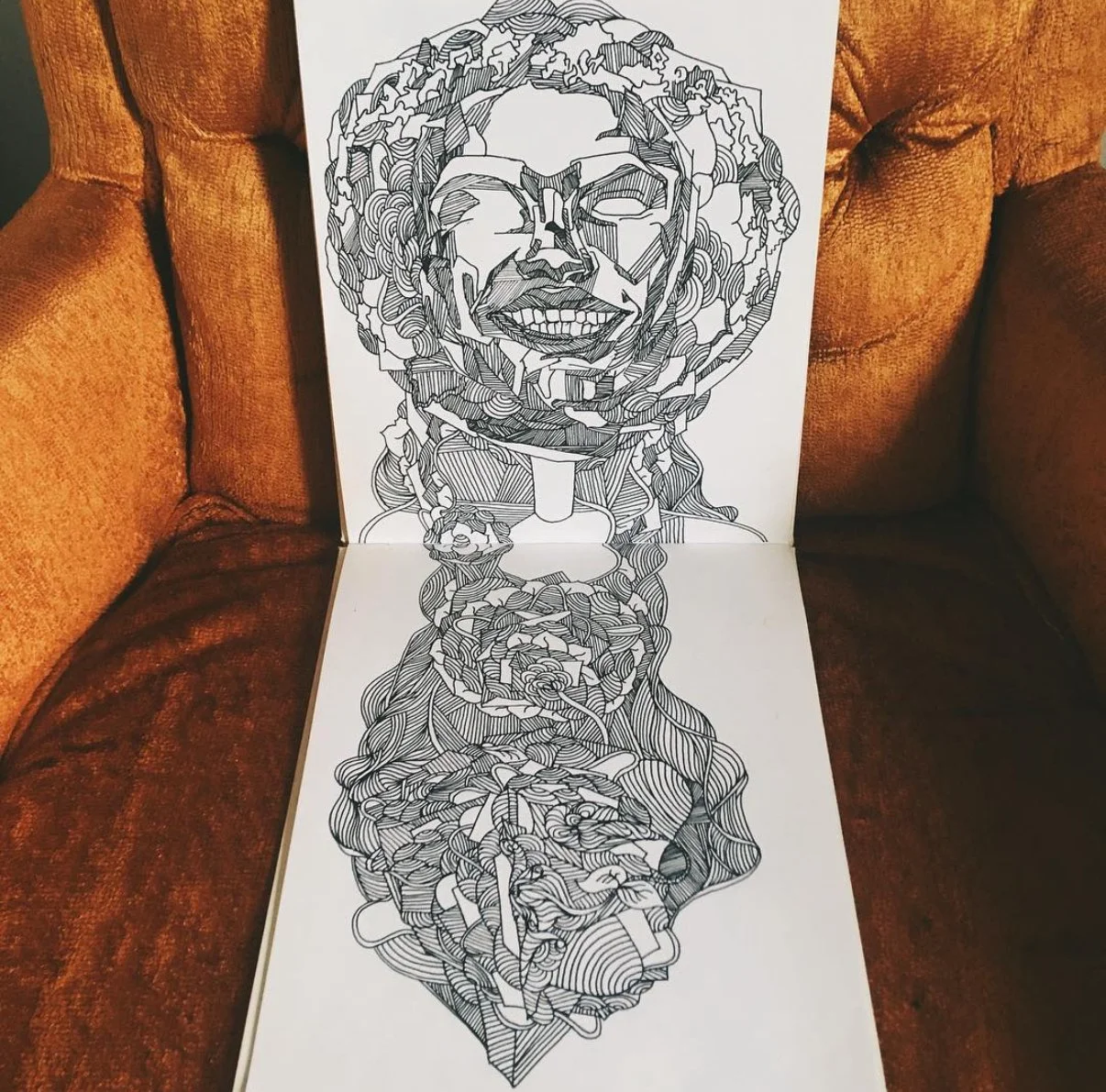

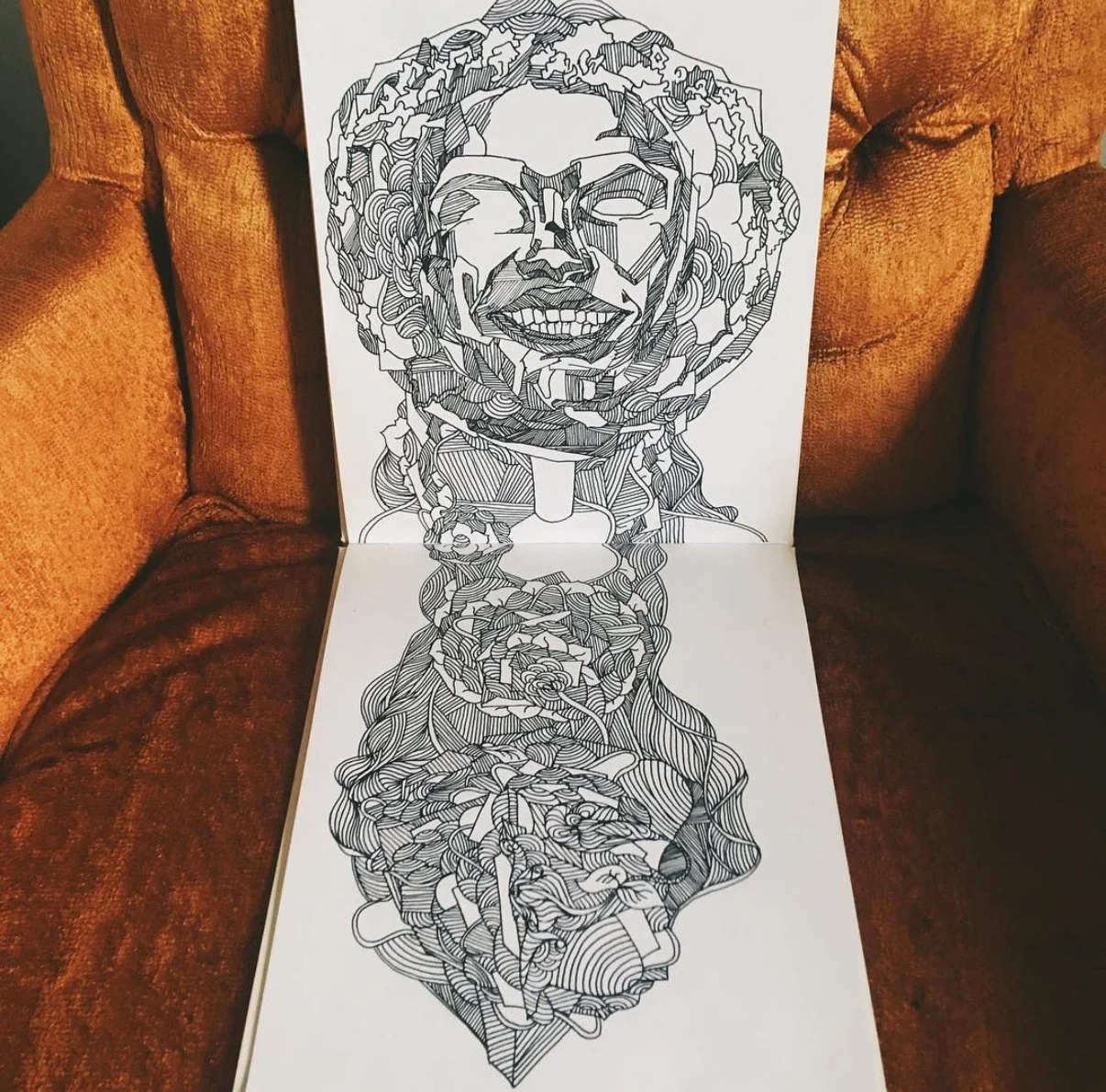

Image caption: CROWN, pen and ink. October 2016. Created after hearing the words, ‘Create, it will free you,’ as I braced myself to face the one-year mark of a deeply traumatic loss.

The irony — or maybe the sacredness — is that the work people see today began in a moment of the deepest pain I had ever known.

That’s the part rarely spoken:

Grief is not the opposite of purpose.

Grief is often where purpose begins.

And yet, grief isn’t linear.

It doesn’t fade.

It revisits.

Especially in seasons like this — seasons of growth, achievement, and transition. When life expands, grief rises to meet it. Not as regression, but as remembrance.

The holiday season magnifies all of it.

For those of us who carry loss, this time of year brings the quiet ache of memory:

losing someone who shaped the core of who you are

the weight of generational responsibility

navigating cycles alone

the loneliness behind the strength

external reminders of the things you don’t yet have

the pressure to be grateful even when your heart feels heavy

It’s not a lack of gratitude.

It’s the body remembering what the calendar doesn’t say out loud.

This year, as I reflect on nearly ten years of MINDART — a company born from my healing, my artistry, my grief, and my resilience — I’m confronting something I didn’t expect:

Image caption: This moment captures me working on CROWN days before the one year anniversary of his transition. Image from November 26, 2016.

I am outgrowing the version of myself who built this company from pain.

Which means I’m outgrowing the vision I held in memory for the last decade — the version shaped by survival, by loss, by the need to make something meaningful out of what broke me.

Letting go of that version is its own grief.

But it’s also an evolution.

As MINDART grows, I grow.

As I grow, the memory of Dro grows too — not as a wound, but as a foundation. Not as a moment frozen in grief, but as a legacy that continues to unfold with every artist we support, every story we amplify, and every space we create.

This moment — this tenth year — is not just an anniversary.

It is a threshold.

A place where grief, gratitude, and becoming converge.

Image caption: Dro and his twin cousin — my forever sister, Shirely — doing what they always did best: laugh, love, and live life to the fullest.

To Dro’s family: I am holding you in love as we cross this milestone with you.

You all became my family long before I understood the language for it. To know Dro was to love him — and I can only imagine what life was like with him 24/7, because even the four years I had with him changed me forever.

Thank you for allowing me to mourn with you, grow with you, and celebrate his legacy alongside you. I carry your strength, your love, and your memory of him with me in everything I build.

Image caption: CROWN evolving into paintings in color — the beginning of rediscovering joy after grief. April 2017.

And to myself — the woman who survived a decade, built a new identity, held space for others while holding her own heartbreak — I honor you too.

My hope in sharing this reflection is simple:

to remind anyone quietly navigating their own duality that it’s okay to hold both the light and the dark. It’s okay to build while grieving. It’s okay to celebrate while remembering. It’s okay to evolve even when the past still tugs at your spirit.

Grief and growth are not opposites.

They are twins.

They shape each other.

They shape us.

And as I step into this next chapter of MINDART — more grounded, more certain, more aligned — I am choosing to carry my grief not as weight, but as wisdom.

A decade later, I’m still becoming.

And that, to me, is the most honest way to honor both the past and the future.

In loving memory,

long live Didro Joseph.

After the Breaking: How Trauma,Neurodivergence and Art Shape a Black Woman’s Journey

Living with complex trauma is like carrying a broken compass. You know where you want to go but cannot orient your steps.

I grew up on a diet of hope and horror. From age eight to thirty I was bullied, assaulted and largely raised by a world that did not know how to care for children, let alone a sensitive Black girl who would become an artist. Abuse and neglect were constants, and the chaos of survival left little room to develop the executive skills that our culture assumes are basic: planning, self‑regulation and initiating tasks. I often misplace keys, procrastinate on deadlines and struggle to keep my home in order. For years I mistook these issues for laziness or character flaws, only to learn that they are common sequelae of unresolved trauma and neurodevelopmental disorders.

On July 28, 2025, I received the clinical diagnoses of complex and compound PTSD and adult ADHD. Something my art and research has been pointing to for years was finally echoed back to me in the most intimate way. My therapist looked at me and said: “You are a walking miracle. I’m not sure if we’ll be able to unpack all of it, but you will heal.” That sentence both broke me and freed me. It named the weight I’ve carried, and it affirmed the possibility that I can move forward lighter.

For me, as a high-producing creative and strategist, this moment wasn’t about labels more than it was about liberation. For the first time, I felt safe enough to begin removing the mask I had worn for decades. The truth is, trauma rewired me on a cellular level. For more than twenty years, I carried wounds no one could see, while pushing myself to deliver, to perform, to excel. And for just as long, I internalized the lie that maybe I was “crazy,” or maybe I was “lazy.”

The diagnosis didn’t define me. It freed me. It affirmed that what I lived through mattered, that my body kept the score, and that my resilience was never a question. I am not broken. I am not lazy. I am not crazy. I am healing. And healing is not only possible: it’s mine.

Researchers have connected childhood maltreatment with long‑term changes in the brain. A study on “cumulative childhood maltreatment” found that higher levels of abuse predicted poorer executive functioning in adulthood (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). These deficits were not explained away by depression or anxiety, meaning trauma itself can disrupt processes like working memory, inhibition and mental flexibility (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). This science gave language to my daily battles. My difficulty planning isn’t a lack of discipline; it is the result of a prefrontal cortex shaped by chronic stress. Neurodivergent traits like ADHD layer on top of trauma, while people with ADHD often experience “time blindness” — a persistent inability to gauge the passage of time and manage tasks — because the prefrontal cortex struggles to coordinate internal clocks (ucihealth.org), and adults with ADHD routinely miscalculate how long tasks will take and feel perpetually behind (chadd.org). But as a business owner, time blindness isn’t cute. It is missed opportunities, frayed relationships and shame.

The shame deepens when you are a Black woman.

An estimated eight out of ten Black women will experience a traumatic event in their lifetime (pbs.org). Psychologist Inger Burnett‑Zeigler reminds us that trauma leaves an imprint on genes and can be passed down across generations (pbs.org). Black women are more likely to face childhood abuse, intimate partner violence and sexual assault (pbs.org), yet we are less likely to receive mental health care (sph.umich.edu). Structural factors—poverty, chronic stress, racism and limited access to culturally competent care—make us more vulnerable to developing post‑traumatic stress disorder (pbs.org). These disparities are not accidents; they are symptoms of a society that devalues Black bodies and dismisses our pain.

Living with complex trauma is like carrying a broken compass. You know where you want to go but cannot orient your steps.

I spent years mismanaging money, staying in toxic relationships and oversharing with anyone who would listen. My entrepreneurial journey was riddled with inconsistent schedules, cluttered spaces and missed deadlines. Some of this chaos is my ADHD, which makes time slippery (psychologytoday.com). But trauma added layers: hypervigilance keeps my nervous system in fight‑or‑flight; dissociation steals time; and chronic shame whispers that I don’t deserve stability. Without treatment, these patterns look like laziness or self‑sabotage. They are in fact untreated disorders. Healing, however, is not just about medication or talk therapy. As an artist I have found that creation is its own medicine.

Art‑making engages sensory systems that integrate emotion, memory and cognition (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Neuroscience shows that the brain remains plastic—capable of forming new connections—and that synaptic plasticity underlies our ability to adapt (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression and PTSD, neuroplasticity is impaired (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Yet creativity and artistic training produce neuroplastic changes in frontal, emotional and sensory circuits (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

If trauma and depression are linked to dysfunctional plasticity, then engaging in art could, quite literally, rewire our brains towards healing.

CROWN - Our Creative Wellness installation at Museum of Science x PureSpark

Art therapy researchers caution against overhyping neuroscience, but they acknowledge that understanding neural mechanisms can improve treatments and help people make sense of how art heals (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In my practice I use what I call brand therapy: a process that helps clients untangle their personal narratives and infuse authenticity into their work. I see parallels between this and art therapy’s emphasis on integrating perception, emotion and cognition.

When survivors create, we reclaim control over our stories.

We map our past, express our emotions through color and texture, and share our narratives with communities. Creativity becomes both mirror and medicine. For Black artists, it is also a form of resistance, declaring that our stories deserve to be told, our visions to be funded and our healing to be prioritized.

The next time you see a colleague who is late to meetings or seems disorganized, consider the unseen load they might be carrying. Unresolved trauma and neurodivergence can erode the executive functions that capitalism demands. Rather than pathologizing individuals, we should build systems that honor healing. That means funding community mental health programs, increasing access to culturally competent care and integrating art and creative therapies into treatment plans. It means recognising that generational trauma is real and providing resources to break cycles. And it means supporting Black women and artists not just with applause but with investment and flexibility.

I am still healing. I still misplace my keys and overbook my calendar. But I now understand that these struggles are not moral failings. They are the scars of trauma and the wiring of a neurodivergent brain. Through therapy, medication and art, I am forging a future where my gifts are not buried under shame. In sharing my story, I hope other survivors see theirs reflected and know that what feels impossible is often an untreated injury. Healing is messy, but with understanding and creative tools it is within reach.